How and why cancers like breast cancer and skin cancer reappear after initially successful treatment remains largely undetermined by the medical community. Research by Dr. David S. Rumschitzki, a Chemical Engineering professor at CCNY’S Grove School of Engineering may help us come closer to an understanding.

Dr. Rumschitzki was the recipient of a 2019 Fulbright U.S. Scholar Grant for his proposal “Theory & experiment for breast cancer dormancy & recurrence.”. In early 2020, Dr. Rumschitzki traveled to Haifa, Israel to study breast cancer recurrence in mice at Technion, Israel School of Technology, with the hope of learning more about dormancy and recurrence of cancers in humans.

Dr. David Rumschitzki.

Dr. Rumschitzki first became interested in studying cancer recurrence while collaborating with Dr. Richard White of The Richard White Lab at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. At his lab, Dr. White bred the stripes out of Zebrafish until they were clear and implanted a fluorescent green tag in a zebrafish melanoma cell line. These bright green tumors made it possible to photograph the fish without killing them. This allowed the cancerous tumors in the fish to be accurately counted and measured as they grew and metastasized. Dr. Rumschitzki’s students injected these cells into the gender and immune status-segregated groups of zebrafish and learned about the growth, shrinkage, and metastasis of these tumors in each of the four groups of fish.

The stripes in the zebrafish are made of melanocytes, the same type of cells that we have in our skin that gives her skin color. And interestingly, the zebrafish can naturally get melanoma with similar gene mutation patterns to human melanoma. So, it’s actually a very good model for human melanoma.

The data from these experiments showed that, due to the female fish’s more robust immune response, there appeared to be a size range of large tumors where female zebrafish would be able to eliminate the tumors and the males wouldn’t. Subsequent experiments aimed at producing such large tumors indeed showed this difference, and data on human melanoma indeed shows that females tend to survive much longer than males after a melanoma diagnosis. Another prediction of the theory is that it provides a testable potential mechanism for dormancy and recurrence. For the fish, the size for dormancy seems to be extremely large, decreasing its interest as an example. To find a candidate animal model to test this theory, Dr. Rumschitzki searched for examples of other animals who exhibited dormancy and recurrence of cancer and came across the phenomenon in a mice breast cancer model.

He found a group at the medical school at Technion, Israel School of Technology in Haifa, Israel who was researching cancers in mice, and asked if they were interested in collaborating with him. He then applied for a Fulbright grant, which was awarded. He began his research at Technion in 2019.

What we wanted to do was get similar data to what we had from the fish. The problem is: mice are not see-through.

At Technion, Dr. Rumschitzki used various methods to study cancerous tumors in mice, including IVIS, CT scans, and post-mortem examination of cancerous tumors. Rumschitzki and his team also used a method where they sacrificed the mice at different times after injecting them with the cancerous cells so they could track the progression of tumor growth.

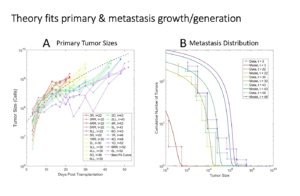

Left: Sizes of the primary tumor in the mammary fat pad of each mouse as a function of time. Right: Number of lung metastases of each size as a function of time since injection of tumor cells into the mammary fat pad. The goal is to follow experimentally and to predict theoretically the generation, growth and merging of tumor metastases in the lungs.

Dr. Rumschitzki plans to continue this research in a new set of experiments with Memorial Sloan Kettering beginning this month, using new MRI techniques. He is also working on a paper that will show the data collected from his experiments in Israel, which will be published this fall.

Christopher Edwards is a Junior at Baruch College, majoring in Journalism and Communication Studies. He is also a reporter for the local Brooklyn news site BK Reader.