In the 1934 film, Imitation of Life, Peola walks away from her mother to gaze into a mirror hanging on the wall. She’s fair-skinned, with hazel eyes and brown hair. Her mother, sensing her angst, asks her what’s wrong. “I want to be white,” she says “like I look.”

Peola is a light-skin Black woman who could be easily mistaken for being white. The character lives in a state of limbo — the child of a dark-skinned black woman whose physical features belie her race. The film centers around her choices and the consequences of those choices as she searches for her identity.

Following the release of this film, Fredericka “Fredi” Washington, the actress who played Peola, spoke out about passing for another race. The actress-writer-activist stood firm against racial passing and stereotyping, something that she herself had to contend with during her career.

Now, City College history professor Dr. Laurie Woodard is writing a biographical study of the New Negro Renaissance actress, “A Real Negro Girl: Fredi Washington and the New Negro Renaissance,” which is set to be published in October by Oxford University Press.

“This project in particular is trying to reconstruct the life and career of an individual Black woman,” Woodard said in an interview.

The book is derived from years of research Woodard has done into Washington’s life. In large part, it is drawn from a scrapbook left behind by the actress-writer, who lived from 1903 to 1994. Also used were photos of her stage work, her old work contracts and scripts, press accounts, and her own writings and films.

Even though she’s been largely lost to history, she was somebody that had an impact,” the professor said. “She sort of dropped out of the narrative and so that’s a big part of what I’m trying to do. I’m trying to put her back into the narrative of Black activism and the New Negro Renaissance.

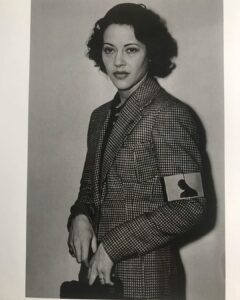

Woodard first began researching Washington as an undergraduate student at Columbia University. On a visit to the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Woodard admired a photography exhibit. One of the photographs was of a beautiful light-skin Black woman in a suit jacket. An anti-lynching armband, with an image of a Black man hanging from a noose, circled her bicep.

“When I saw this photograph, I said, ‘My goodness, who are you?’” Woodard said. “Who is this? This pretty girl with this ugly symbol on her arm.”

That image of Washington sparked Woodard’s lifelong interest in her activism. She went on to write a three-page paper about Washington for one of her undergrad classes. Then, a 10-page paper. Then, her undergraduate thesis. Then, her Yale University dissertation. And, finally, her book.

“It has been all-consuming, much to the chagrin of everyone that knows me,” she said. “My sister used to say, ‘Oh, for heaven’s sake, we all know all roads lead to Fredi.’”

Washington began her performance career as a chorus line and nightclub dancer in the 1920s. She transitioned to stage and film acting in the late ‘20s, though she had limited roles to audition for due to her complexion, as well as the few opportunities for black dramatic actresses in general. Like her character Peola, she had to make the choice between hiding her identity and passing as white or standing proud as a Black woman.

She refused to pass herself off as something she wasn’t, as well as to play roles that stereotyped Black women as “mammies” — roles she likely wouldn’t have been chosen for anyway due to her skin color.

She refused to pass herself off as something she wasn’t, as well as to play roles that stereotyped Black women as “mammies” — roles she likely wouldn’t have been chosen for anyway due to her skin color.

In the 1930s, Washington co-founded the Negro Actors Guild and worked as the organization’s executive secretary for several years. She then went on to become the administrative secretary of the Joint Actors Equity-Theater League Committee on Hotel Accommodations for Negro Actors.

By the ‘40s, while continuing to appear on the stage, Washington was a journalist, writing primarily for the Harlem-based Black newspaper The People’s Voice.

She wrote columns and features about the portrayal of Black people in popular media, including stereotyped roles like “mammies.” She called for better roles for Black actors, an end to racial discrimination in the military, and opposition to white supremacy. Other of her works were focused on entertainment and culture, as well as lynching and American “homegrown systems of fascism and tyranny.”

Woodard has spent years reconstructing Washington’s life. While not the same as STEM research, her archival research has been detailed, in-depth, and determined.

“I think that there’s a little bit more methodological overlap between the humanities and STEM than we might normally think,” she said. “Just in the broadest terms, we do the same things that people do in STEM — we pose questions and we look for answers.”

Amanda is a student at the CUNY Graduate School of Journalism, where she’s studying health & science reporting and broadcast journalism. She graduated from Baruch College in May 2022, where she double majored in journalism & creative writing and political science and double minored in environmental sustainability and communication studies. She has been published in City & State, BORO Magazine, Bklyner, The Canarsie Courier, the New York City News Service, PoliticsNY, Gotham Gazette, Bushwick Daily, DCReport, News-O-Matic, The Queens Daily Eagle, Tower Times, The Ticker, and Dollars & Sense Magazine.