CCNY Professor Dr. Irina Carlota (Lotti) Silber’s 30-year commitment to exploring the aftermaths of Central American political conflict and how people build meaningful lives in the pursuit of justice has led her to produce two new books, After Stories: Transnational Intimacies of Postwar El Salvador (2022) and Higher Education, State Repression, and Neoliberal Reform in Nicaragua: Reflections from a University Under Fire (2023).

Silber is chair of the Department of Anthropology, Gender Studies and International Studies at the Colin Powell School for Civic and Global Leadership.

The professor’s interest in El Salvador politics led her to study their post-war communities and how they struggled to find peace after a long period of civil unrest. This interest was sparked when Silber was an undergraduate student, around the time the Chapultepec Peace Accords were signed, effectively ending the 12-year Civil War in El Salvador. The treaty promised peace between the U.S.-backed Salvadorian government and the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front, a combination of five left-wing militant groups. In “After Stories: Transnational Intimacies of Postwar El Salvador”, she builds on her earlier research on disillusionment. Everyday Revolutionaries: Gender, Violence, and Disillusionment in Postwar El Salvador focuses on what she refers to as the 1.5 insurgent generation, the children born during the end of the war, and how their upbringing could lead to a more just future.

Her new book questions the powerful stereotypes about Salvadorans in El Salvador and in the diaspora, especially in the United States, that flatten and dehumanize their histories, culture, and experiences. She addresses issues of violent crime, immigration, and remittances by documenting the legacy of the generation after the war.

The book is really an ode to repopulated communities in Chalatenango, sites of destruction and wartime battle, but also sites of extraordinary activism where the lives and perspectives of everyday former revolutionaries can help us imagine what a better world could look like.

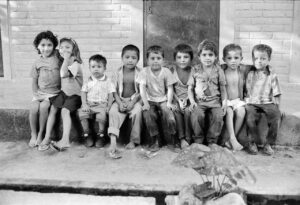

Children in El Salvador. Photo by Antonio Rossi

During the early 1990s, there was a lot of rhetoric about unauthorized immigrants being denied asylum, especially in Washington DC. One of Silber’s professors at the time inspired her to think critically about political and legal anthropology. What started as a class project on community and human rights organizations supporting Salvadoran migrants’ political asylum cases “created a long-term academic solidarity and commitment to Central America.”

As a doctoral student at New York University, she began her fieldwork research in El Salvador in 1993 after she received the Tinker Field Research Grant from New York University, and later received awards such as the Fulbright-Hays, Inter-American Foundation, the Charlotte Newcombe award, and postdoctoral fellowships including a Rockefeller at the Virginia Foundation for the Humanities.

“That first award transformed my life,” she said. “It sparked a lifelong process of what now we talk about as public anthropology, engaged anthropology, looking at post-war processes, with communities that had recently laid down their guns and were trying to rebuild their lives.”

El Salvador. Photo by Antonio Rossi

When doing her research in El Salvador, Silber realized that it was critical to understand at a granular level the experiences of reconciliation when it came to rebuilding a community after a decade of war. Silber also said that it was important to give space to deconstruct any preconceived notions of El Salvador and to understand that over $6 billion in military aid from the U.S. exacerbated this armed conflict and as a result led to the death of over 75,000 people.

For Silber, when it comes to research her mantra is that it’s important to step up but, also step aside. Humility and solidarity, or in Spanish acompañamiento are valuable to decentering what we know but, also using our power in academia.

“Higher Education, State Repression and Neoliberal Reform in Nicaragua: Reflections from a University Under Fire” examines the repression that exists in higher education around academic freedom of thought. As Human Rights organizations document, Nicaragua has experienced an authoritarian regime filled with violence that accelerated when students took to the street to protest against the government in 2018.

We really tried to show the ways in which neoliberal governance and its obsession with accreditation, numbers, and so on coalesced with a militarized repression, and how devastating that can be for the education of the next generation.

Threats to academic freedom like the ones discussed in her books are a problem that can be seen all over the Americas. In the United States, Florida is trying to ban lessons about race and gender as part of the governor’s campaign against “wokeness” and “critical race theory.”

The book attempts to see what type of conversations and policies are needed to combat neoliberalism and repression in higher education. One of its goals is to provide a vision and best practices for higher learning across the Americas, where universities are under attack as increasingly documented.

Silber who is Argentine-born and U.S. raised has dedicated herself to a long-term commitment and academic solidarity with Central America.

As a 1.5 immigrant, as a child of migrants, I came here when I was very young, and socialized into a real awareness of Latin American politics and military dictatorships and repression and the critical importance of working together in the pursuit of justice across borders

Malina Seenarine is a recent graduate of Baruch College where she studied journalism and minored in theater. In addition to writing for The RICC, she’s a contributor for Baruch’s award-winning Dollars & Sense Magazine and wrote for the arts and news section of Baruch’s student-run newspaper, The Ticker. She’s also written for FSR magazine.