Over 150 years ago the French physician Paul Broca discovered that a region in the left frontal lobe of the brain was important for language; a breakthrough in understanding human verbal communication. Today we believe that the brain assigns distinct language tasks to the two halves of the brain, a division of labor called lateralization. It remains one of the least understood functions of the brain, and at the Biology Department at City College, Dr. Hysell V. Oviedo studies mammalian animal models with communicative abilities to discover evolutionary conserved neural mechanisms.

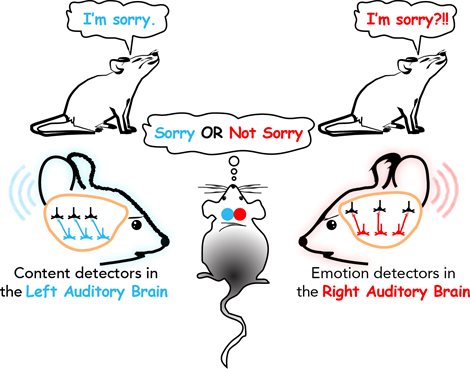

Recent discoveries have shown that rodents make use of lateralized vocalization processing, like humans. Lateralization allows for the left auditory cortex (a sound-processing area in the brain’s neocortex) to process the meaning of speech, while the right deciphers the emotional content. “Rodents also offer the advantage of having brain organization homologous to humans, share similar developmental programs, and can be studied using powerful genetic and molecular tools.”

Dr. Oviedo is particularly interested in the division of labor of vocalization processing and how its development can go awry. Her approach is to identify lateralized circuit-motifs in the auditory cortices and link them to specific sound processing functions. Parsimoniously the two halves of the brain should be identical in structure and function. Dr. Oviedo reasoned that screening for differences would reveal specializations related to lateralized processing. Utilizing cutting-edge techniques for high-throughput circuit mapping, functional imaging, optogenetics, RNAsequencing and behavior Dr. Oviedo can compare the development, patterns of connectivity and operations of the left and right auditory cortices. One of the biggest challenges the brain tackles in language processing is capturing information from the fleeting auditory world: the basic unit of speech (phonemes) lasts only tens of milliseconds. It is believed that lateralization is a solution to this challenge: parallel processing speeds up decoding of speech content.

Dr. Oviedo is particularly interested in the division of labor of vocalization processing and how its development can go awry. Her approach is to identify lateralized circuit-motifs in the auditory cortices and link them to specific sound processing functions. Parsimoniously the two halves of the brain should be identical in structure and function. Dr. Oviedo reasoned that screening for differences would reveal specializations related to lateralized processing. Utilizing cutting-edge techniques for high-throughput circuit mapping, functional imaging, optogenetics, RNAsequencing and behavior Dr. Oviedo can compare the development, patterns of connectivity and operations of the left and right auditory cortices. One of the biggest challenges the brain tackles in language processing is capturing information from the fleeting auditory world: the basic unit of speech (phonemes) lasts only tens of milliseconds. It is believed that lateralization is a solution to this challenge: parallel processing speeds up decoding of speech content.

What makes us unique as an animal is that we can use sound pressure waves to communicate meaning. When that ability goes awry in developmental disorders, from something so mild as Asperger’s to low-functioning autism, it’s fascinating to know what went wrong.

The research conducted by Dr. Oviedo could be beneficial for understanding communication disorders. They are the most common disability in children, affecting 8-12% of preschoolers. This is a great concern in lower income groups according to Dr. Oviedo. In this population, communication deficits are more prevalent, under diagnosed and go untreated for longer. “Children don’t get the right help early on and have less of a possibility of getting the therapy they need to overcome neurodevelopment disorders.”

Early intervention is key since that is when language circuits are developing.

Dr. Oviedo’s project will establish developmental milestones during the formation of the brain’s divide and conquer vocalization processing functions in mice. “We know the critical time period for humans is the first 9 years of life. The goal is to learn the best window of opportunities for interventions.” Her research could lead to the discovery of genes or molecular pathways that regulate the development of language processes shared between mice and humans that could lead to improved treatment.

Credit – H. Lebreault

Regarding career advice, Dr. Oviedo advises doctoral students to consider one year of post-doctorate research. “Even if you’re not staying in academia, trying a new lab environment helps to finalize your maturity as a scientist.”

You have to know if curiosity is part of who you are, if you live to ask questions. What drives me everyday is a need to ask questions, do experiments, and find answers.

Dr. Oviedo’s team has received funding from the Whitehall Foundation and the National Science Foundation. Collaborators include Dr. Nicolas Renier in the ICM Institute in Paris, and Dr. Il Memming Park in Stony Brook. Dr. Oviedo is also launching a collaboration with Dr. Robert Froemke from New York University to study the neuroplasticity of social behavior.

Edgar Llivisupa is a journalist based in New York who joined the RICC in May 2021. Currently a Journalism and Spanish major at Baruch College he has covered business, science, culture and transit, in addition to living in Spain for two years to improve his Spanish proficiency.